Why Do Jewish Women Wear Wigs? | 7 Common Reasons

Did you know that in traditional Judaism, married women are required to cover their hair as a sign of modesty? This practice, rooted in ancient teachings, is not simply cultural, it’s deeply religious.

According to Jewish law (Halacha), hair is considered a private aspect of a woman’s body, meant only for her husband to see.

The concept stems from Tzniut, a Jewish principle of modesty in behaviour and appearance. Tzniut governs many aspects of life, particularly how women present themselves in public.

Covering one’s hair is viewed as a spiritual and modest act that enhances a woman’s dignity and reflects her respect for divine commandments.

What Is a Sheitel and Why Do Jewish Women Use It?

A sheitel is the Yiddish word for a wig, specifically worn by Jewish women after marriage as a substitute for uncovering their natural hair.

While some may opt for scarves, hats, or tichels (traditional head wraps), wigs are popular in many Orthodox Jewish communities due to their practicality and appearance.

Some sheitels are indistinguishable from natural hair, which has sparked debate in more conservative circles. Nevertheless, they are widely accepted in various Jewish denominations as an appropriate way to fulfil the religious requirement of hair covering.

Top 7 Reasons Why Do Jewish Women Wear Wigs

The practice of wearing wigs, commonly referred to as sheitels by Jewish women, especially after marriage, is grounded in centuries of tradition and religious law.

While it may appear as a simple fashion choice from the outside, each reason behind it carries deep spiritual, cultural, and personal significance. Let’s take a closer look at the top seven reasons why Jewish women wear wigs:

1. Observing Modesty (Tzniut)

At the heart of this practice is the Jewish concept of Tzniut, which translates to modesty. In Judaism, modesty isn’t limited to how one dresses, it extends to speech, behaviour, and presentation.

A married woman’s hair is traditionally considered a sensual and private aspect of her body. Covering it, therefore, becomes a way to maintain dignity and avoid unnecessary attention in public spaces.

Wigs serve as a practical and acceptable way to fulfil this commandment while allowing women to maintain a presentable and socially acceptable appearance.

The act of covering hair is seen not as oppression, but as an empowerment, a voluntary commitment to one’s faith and values.

2. Sign of Marital Status

Just as a wedding ring signals that someone is married, covering one’s hair functions similarly in many Jewish communities.

The transition from uncovered to covered hair marks a significant life milestone. It symbolises a woman’s entry into married life, where certain aspects of her appearance become sacred and reserved for her partner alone.

In many Orthodox and Hasidic circles, the wig serves as a clear public declaration that a woman is married, much like traditional attire or accessories in other cultures might do.

3. Fulfilment of Halachic Law

Halacha, or Jewish religious law, outlines a variety of practices and commandments that guide daily life.

One such commandment, derived from interpretations of the Talmud and other rabbinic texts, is that a married woman must cover her hair in public.

While the specific texts don’t mandate wigs as the method of covering, wigs have become one of the most commonly accepted ways to fulfil this obligation.

Over time, prominent rabbis have issued rulings affirming the acceptability of sheitels. Some even suggest that wigs are preferable to scarves or hats because they offer full coverage and are less likely to slip or shift during the day.

However, interpretations can vary widely between communities, and not all authorities agree on the use of wigs.

4. Sense of Identity and Community

Wearing a wig can help foster a sense of belonging. In tightly-knit Jewish communities, especially among the Orthodox, religious attire plays a key role in group identity.

A woman who wears a sheitel often signals her adherence to the shared values, customs, and lifestyle of her religious group.

It’s also a means of continuity of carrying forward the practices of one’s ancestors and embedding oneself in a larger historical and spiritual narrative. For many women, it’s not just about modesty but about solidarity and cultural preservation.

5. Protection of Personal Dignity

Some women view hair covering as a form of emotional and spiritual protection. By keeping certain parts of their body private, they maintain a separation between their public and private selves.

The act becomes one of personal dignity, reminding them and others that their self-worth isn’t tied to external beauty alone.

Additionally, in public or professional environments, the wig allows women to interact confidently while still adhering to their religious beliefs.

It offers a kind of shield, protecting their inner sanctity from being overly exposed in a world that often prioritises physical appearance.

6. Practicality and Acceptance

Wigs provide a practical alternative to traditional hair coverings like scarves or hats. In modern society, especially in professional and urban settings, a sheitel blends seamlessly into the environment.

It allows Jewish women to participate in the workforce, attend events, and engage with the wider world without constantly adjusting or explaining their attire.

Moreover, today’s wigs are made from high-quality synthetic or natural hair, offering comfort, style variety, and even temperature control.

Many women prefer them because they’re easy to maintain and more consistent in appearance than other types of coverings.

7. Expression of Religious Pride

While some view wigs as a mere obligation, others wear them with a sense of pride and purpose. For many Jewish women, the sheitel isn’t a symbol of restriction, it’s a badge of honour.

Choosing to cover their hair is a daily reaffirmation of their beliefs, a way to express their spirituality with confidence.

This reason is particularly strong among younger observant women, who often approach the tradition with renewed meaning.

They may customise their sheitel, experiment with styles, and incorporate it into a broader sense of self-expression rooted in faith.

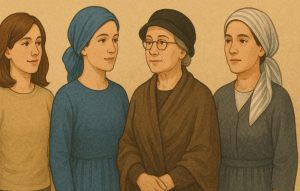

How Do Practices Differ Across Jewish Communities?

Hair covering among Jewish women is far from a one-size-fits-all tradition. The customs surrounding it vary significantly across Jewish communities, shaped by geography, religious denomination, and cultural heritage. While the principle of modesty (Tzniut) is a common thread, its expression differs.

Hasidic Communities

In Hasidic communities, particularly in Eastern Europe and the United States, hair covering is considered non-negotiable for married women.

Most wear wigs (sheitels) as their primary covering, and some add an extra layer of modesty by wearing a hat, scarf, or headband over the wig.

This “double covering” is believed to enhance modesty and reduce any resemblance to uncovered hair.

Modern Orthodox Communities

Modern Orthodox Jewish women also observe hair covering, but there is generally more flexibility in both practice and style.

Some wear wigs, others opt for scarves or hats, and a portion may allow a small portion of natural hair to show.

The emphasis is still on modesty, but with a balanced approach that allows for personal expression and integration into modern society.

Sephardi Communities

Sephardic Jews, those with roots in Spain, North Africa, and the Middle East, often adhere to more conservative hair-covering practices.

Many Sephardi rabbis discourage or even prohibit the use of wigs, viewing them as too close to real hair and therefore not modest.

Instead, scarves (tichels) and decorative headwraps are more common, often in vibrant colours and traditional fabrics.

Reform, Liberal, and Secular Jewish Communities

In these groups, hair covering is typically seen as a cultural or symbolic tradition rather than a religious obligation.

Most women in these communities do not cover their hair after marriage. If they do, it is often for personal or spiritual reasons rather than communal expectation.

These differences highlight how adaptable Jewish traditions can be, shaped by centuries of diaspora, interaction with host cultures, and evolving religious interpretations.

How Have Jewish Hair Covering Traditions Evolved Over Time?

The practice of hair covering among Jewish women is ancient, dating back to Biblical times but its form, function, and fashion have transformed dramatically throughout history.

Biblical and Talmudic Times

Early Jewish texts, including the Torah and Talmud, make references to women covering their hair as a sign of modesty and marital status.

In Numbers 5:18, the priest uncovers a woman’s hair during a ritual, implying that it was normally covered. This served as one of the earliest religious justifications for hair covering in married life.

Medieval and Early Modern Period

During the medieval era, Jewish women in Europe and the Middle East used veils, kerchiefs, and headscarves to cover their hair.

The methods were often influenced by the dominant culture. In Muslim lands, for instance, Jewish women adopted regional veiling practices. In Europe, bonnets and caps were common, aligning modesty with the styles of the time.

The use of wigs began to emerge in 17th and 18th century Europe, when fashion trends changed. Jewish women adopted wigs as a means of staying modest while appearing elegant in society.

Rabbinic opinions varied—some viewed wigs as acceptable, while others raised concerns that realistic-looking wigs undermined the purpose of modesty.

Modern Era

In the 20th and 21st centuries, technological advancements transformed the production and style of wigs. Today, sheitels come in a wide range of lengths, textures, colours, and materials from synthetic fibres to high-end human hair.

Many look virtually indistinguishable from real hair, which has both supporters and detractors in the Jewish world. Women now also have access to headscarves, hats, and pre-tied tichels in various prints and styles.

There’s been a resurgence of choice, with some women embracing more traditional head coverings and others choosing wigs that align with professional and aesthetic expectations.

The evolution of these traditions reflects not just religious adherence, but the dynamic intersection between faith, fashion, and cultural identity.

Why Is the Sheitel Controversial in Some Jewish Circles?

Despite its widespread use, the sheitel remains a point of contention in certain Jewish communities. The heart of the debate lies in a tension between appearance and intent whether a wig truly upholds the modesty that Jewish law intends to preserve.

Too Similar to Natural Hair?

One of the main criticisms is that modern wigs—especially those made from human hair look too much like a woman’s natural hair. For some rabbis, this undermines the very purpose of covering one’s hair.

If the sheitel is styled attractively or mimics natural beauty, does it still count as modest? This question has sparked numerous rabbinic discussions over the years.

Rabbinic Prohibitions

Some influential Sephardic and Haredi rabbis have ruled against the use of wigs altogether. For example, Rabbi Ovadia Yosef, a leading Sephardic authority, strongly opposed the use of sheitels and advocated for scarves or hats instead.

His argument was based on both legal and spiritual grounds he believed wigs could mislead others and fail to fulfil the modesty requirement.

Cultural vs. Religious Values

Others argue that wigs have become too fashion-driven, blurring the line between religious observance and secular trends. With high-end wigs sometimes costing thousands of pounds, critics question whether the focus has shifted from modesty to vanity.

Defences of the Sheitel

On the other hand, many rabbis and scholars defend the use of wigs, arguing that they allow women to fulfil religious law while engaging fully in modern life.

For working women, particularly in professional fields, wigs offer a practical and respectful solution that doesn’t compromise their public presence.

Some also see the controversy as part of a broader conversation about personal agency in religious practice.

For many women, the choice to wear a wig is not about impressing others, but about balancing religious commitment with lifestyle and identity.

Comparison of Hair Covering Practices Across Jewish Sects

| Jewish Group | Wig (Sheitel) | Scarf (Tichel) | Hat | No Cover |

| Hasidic | Common | Sometimes | Yes | No |

| Modern Orthodox | Sometimes | Sometimes | Yes | No |

| Sephardi | Rarely | Often | Yes | No |

| Reform / Secular | Rarely | Rarely | No | Yes |

Final Thoughts on the Cultural and Religious Importance of Wigs

Wearing a wig may seem unusual to those unfamiliar with Jewish traditions, but for many Jewish women, it’s a deeply meaningful choice.

Whether for religious compliance, cultural pride, or personal expression, the sheitel continues to serve as a powerful symbol of devotion, dignity, and identity.

Frequently Asked Questions

Do all Jewish women wear wigs after marriage?

No. While many do, especially in Orthodox circles, others may opt for scarves, hats, or no covering depending on their level of observance and community norms.

Are wigs mandatory in Judaism?

No. Hair covering is often required, but the method (wig, scarf, hat) is up to interpretation and tradition.

Why are wigs more accepted than other coverings in some groups?

Wigs provide a balance of modesty and modern appearance, which suits the needs of many Orthodox women.

What’s the difference between a sheitel and other hair coverings?

A sheitel is a wig specifically worn for modesty by Jewish women, while other coverings include scarves, hats, and wraps.

Can wigs be fashionable and still religiously acceptable?

Yes. Many women select sheitels that meet modesty standards while also suiting their taste and lifestyle.

Are wigs more common in certain countries or regions?

Yes. Wigs are more common in the US, UK, and Israel among Orthodox communities, while scarves dominate in many Sephardi communities.

How do younger generations view this tradition?

Views vary some uphold it proudly, others reinterpret it with a modern lens, blending tradition with personal expression.